When the Hartford Civic Center roof went south in 1978, the New England Whalers went north.

The Whalers-Carolina Hurricanes are celebrating something of a milestone this season, this being the 20th anniversary of the Hartford Whalers’ final season in Connecticut.

But when it comes to relocation, the franchise really has the market cornered. In both Hartford and Tobacco Road, the Whaleicanes have had a host of homes away from home.

Several NHL franchises have found themselves playing in unique arenas over the years. Perhaps the most unusual was the Tampa Bay Lightning playing for three seasons inside the dome at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, a building that’s barely suitable for Major League Baseball, let alone hockey.

But the true hockey nomads were the Whalers, who found themselves thrown out into the snowy cold of Hartford in 1978 due to a collapse that had nothing to do with allowing multiple goals in the third period.

The Whalers were still the New England Whalers in 1978, playing in the World Hockey Association, but with eyes on merging into the NHL for the 1979-80 season, along with Edmonton, Winnipeg and Quebec.

But that almost came crashing down on the early morning of Jan. 18, 1978. What did actually come crashing down was the ill-conceived roof of the Civic Center.

Built in 1975 and seating just over 10,000 for hockey, the arena had just held a University of Connecticut men’s basketball game during a raging snowstorm on the night of the 17th.

Fortunately for the 4,746 in attendance, fate chose to wait another six hours. As snow continued to pile up on the Civic Center roof, the structure gave way about 4 a.m., dropping the roof into the bowl below.

Miraculously, no one was injured in the collapse, but suddenly the Whalers were without an arena to call home at mid-season.

Enter the Springfield Civic Center, located roughly 30 miles north of Hartford. The arena allowed the Whalers to finish out the 1978 season, then play its entire 1978-79 schedule in the Whalers’ final season in the WHA.

Whalers fans in Hartford continued to support the franchise despite the unusual relocation, with 4,200 season-ticket holders creating a group called the “91 Club,” in honor of Interstate 91 that connected Hartford to Springfield. Whalers owner Howard Baldwin created “membership” certificates for the 91 Clubbers, a tribute to the fact that less than 300 season-ticket holders canceled their plans in wake of the collapse.

Even as the Whalers accepted membership into the NHL in the summer of 1979 and officially changed their name to the Hartford Whalers, the Springfield connection continued will into the Whalers’ inaugural NHL season, as the refurbished Hartford Civic Center did not officially open until Feb. 1980.

By 1997, however, the NHL dream would die in Hartford, as team owner Peter Karmanos moved the Whalers to Raleigh, North Carolina for the 1997-98 season. Now called the Carolina Hurricanes, the team faced another relocation dilemma. While Karmanos was determined to flee Hartford, it would be two years before the Hurricanes would have their own venue, the Raleigh Entertainment & Sports Arena (now PNC Arena).

In the interim, the Hurricanes played their home games for its first two seasons at the Greensboro Coliseum in Greensboro, N.C.

The Hurricanes’ temporary home was the last in a trio of transient NHL teams. The 1990s saw the NHL undertake a massive expansion into the southern United States, as teams like Hartford, Quebec, Minnesota and Winnipeg made new homes in Carolina, Denver, Dallas and Phoenix.

But other franchises began popping up in sunny climates like Miami, Anaheim, Nashville and San Jose.

The latter entered the NHL in 1991, when the San Jose Sharks became the first Bay Area franchise since the Golden Seals left Oakland in 1976.

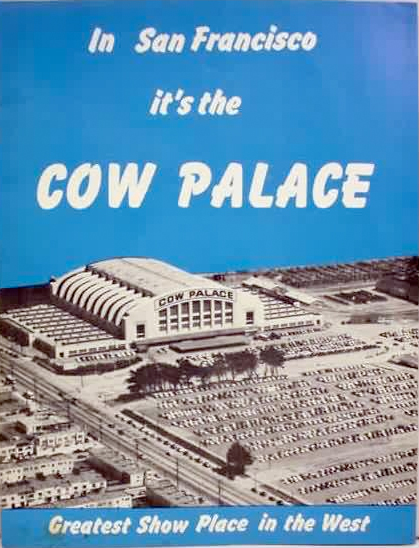

How determined was the NHL to successfully integrate the Bay Area into the modern NHL? The Sharks played their first two seasons (1991-93) at the Cow Palace just outside San Francisco, while San Jose Arena was under construction.

The Cow Palace was certainly an interesting choice. It was Oakland Coliseum Arena that had hosted the Seals from 1967, until their move to Cleveland in 1976. The Cow Palace had been rejected as a host site by the NHL in 1966, not least of which because the arena’s dimensions did not allow for a regulation size NHL playing surface.

But starting in 1991, the Cow Palace served the NHL well, selling out nearly every game for the two seasons the Sharks played in the ancient arena.

As the Sharks moved into their permanent home in 1993, another expansion franchise found a temporary home in the Tampa Bay area. Years before the Rays would call Tropicana Field their home in Major League Baseball, the Lightning—who played the 1992-93 season at Expo Hall in Tampa—and the Tampa Bay Storm of the Arena Football League were the first official tenants of the 45,000-seat domed stadium.

Called the Thunderdome during the Lightning’s three seasons in St. Petersburg, the arena used its configuration as a football/baseball stadium to set various attendance records until the advent of the Heritage Classic in 2003. The Thunderdome still holds the record for largest Stanley Cup playoff attendance with 28,183 for a game against the Flyers in 1996.

This article originally appeared in the weekly Arena Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the free weekly newsletter.