After months of steadfastly denying any interest in a new arena, MSG officials apparently are opening the door ever so slightly to a new Madison Square Garden next to the existing one—but there’s no plan on the horizon, and plenty of obstacles present.

New York City officials have raised the issue of a massive renovation project that would see a new Garden as part of megadevelopment removing the current Penn Station and MSG. The “new” Penn Station, which opened in 1963 and replaced the venerable Penn Station originally designed by McKim, Mead and White, has never been a beloved train station; New Yorkers tolerate it but they certainly don’t love it. Even New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has deemed it a “hellhole.”

The rationale for considering this massive makeover: MSG’s 10-year permit to run the building expires in July. The importance of this permit is debatable: some in City Hall see this as a wedge to force MSG to accept a new arena and free up the valuable real estate, but MSG officials argue the city really doesn’t have the power to force a relocation of the arena. When we first reported on this last summer, MSG officials were adamant in their opposition to the project, saying that MSG owns the land beneath the arena and can’t be forced to vacate the real estate. (Indeed, the permit expiration seems to be a way to air grievances about the current MSG management, such as using facial recognition technology to bar attorneys involved in arena lawsuits from entering the facility.)

But MSG really isn’t the target here: New York City would love to see a new train terminal built at the Penn Station site, and removing MSG is key to a project of that scale. Things are certainly in flux, however: the original plan to construct 10 new office towers a la Rockefeller Center has been put on hold by developer Vornado, saying that current economic conditions and the uncertain future of office space needs is forcing a reconsideration of the project. But that’s not stopping Hochul and the Empire State Development agency from pursuing the massive development, though it is clear the emphasis has shifted from tall towers to a Penn Station redevelopment—which by definition means changes to Madison Square Garden:

“The improvement of Penn Station should not be beholden to a business cycle,” said Alexandros Washburn, the former chief urban designer at the Department of City Planning and director of the Grand Penn Community Alliance, a group that supports a full overhaul of the train station.

In one vision, Madison Square Garden would be demolished and rebuilt on a site in Hudson Yards, on the Far West Side of Manhattan. In its place, a new Penn Station would be built below a sprawling green space — similar in scale to Bryant Park — on the remains of the venue. The plan would address commuters’ concerns about congestion and train capacity, which Vornado’s project does not, Mr. Washburn said.

While it is clear MSG officials aren’t thrilled about an out-of-the-way location in Hudson Yards, apparently a potential new arena next door to the old one could be of interest, as MSG Executive Vice President Joel Fisher met with Manhattan Community Board 5 last week and opened the door—very slightly—to a new MSG on the Pennsylvania Hotel site:

“Well that would probably satisfy us,” said Fisher. “But ultimately, who’s going to pay for that? Where is the money? That plan hasn’t come to us. But that would satisfy being right on top of a transportation hub.”

“This was certainly, for us, the first time that we’ve heard MSG express that they would consider this option,” CB5 Chair Layla Law-Gisiko told Crain’s New York Business.

Admittedly, this is a small shift with plenty of qualifiers. And there doesn’t seem to be a huge will among New York City politicos for forcing the arena to the far west side, with many admitting now that a new Penn Station doesn’t automatically mean displacing Madison Square Garden—and with a price tag of $8.5 billion, there may not be taxpayer appetite for relocating the arena, either.

A little MSG history for you. The MSG saga begins in April 27, 1874 when noted showman P.T. Barnum and an investment group took over the open-air New York and Harlem Railway Station and New York and New Haven stations at Park Avenue South and 26th/27th streets, combining them to create an exhibition hall, the Great Roman Hippodrome. As with everything associated with Barnum, the programming is a mix of the high and the low, with events ranging from ostrich and elephant races to sporting events like bike races to the American debut of noted composer Jacques Offenbach.

Ownership of the Hippodrome passed through several owners, ending up in the hands of William Kissam Vanderbilt, grandson of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. It was William Kissam Vanderbilt who renamed the old Hippodrome to Madison Square Garden, and it was Vanderbilt who put together the financing syndicate (which included J.P. Morgan, W.W. Astor and Andrew Carnegie) created the second Madison Square Garden, hiring noted architect/designer Stanford White to create the Beaux-Arts style facility, opening in 1890. MSG II was one of White’s notable accomplishments, but it also led to his demise: after embarking in an affair with 16-year-old Elizabeth Nesbit—the girl in the red velvet swing—White was later shot to death at MSG by Harry Kendall Thaw, who had married Nesbit but was jealous of White.

Despite the artistic success of MSG II, it was a financial failure, eventually torn down to make way for the New York Life Building. Still, there certainly was a market for arena entertainment, and the creators of MSG III took a more pragmatic and less artistic approach to arena design, creating a larger, more spacious facility on cheaper land at 50th and 8th Avenue, opening in 1925. It was a barn, with a capacity over 18,000, and despite plenty of obstructed-view seats and poor ventilation, it attracted the biggest events of the day under the direction of legendary promoter Tex Rickard. His approach was to fill the arena with as many events as humanly possible: pro and college basketball, boxing, religious revivals, biking, political rallies, musical acts, and even the installation of water tanks for open swimming. This was where Marilyn Monroe famously sang “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy and where the pro-Nazi German American Bund rallied to promote American fascism in 1939; two years later aviator Charles Lindberg delivered an America First speech calling for the United States to stay out of World War II. There was always something happening at the Garden.

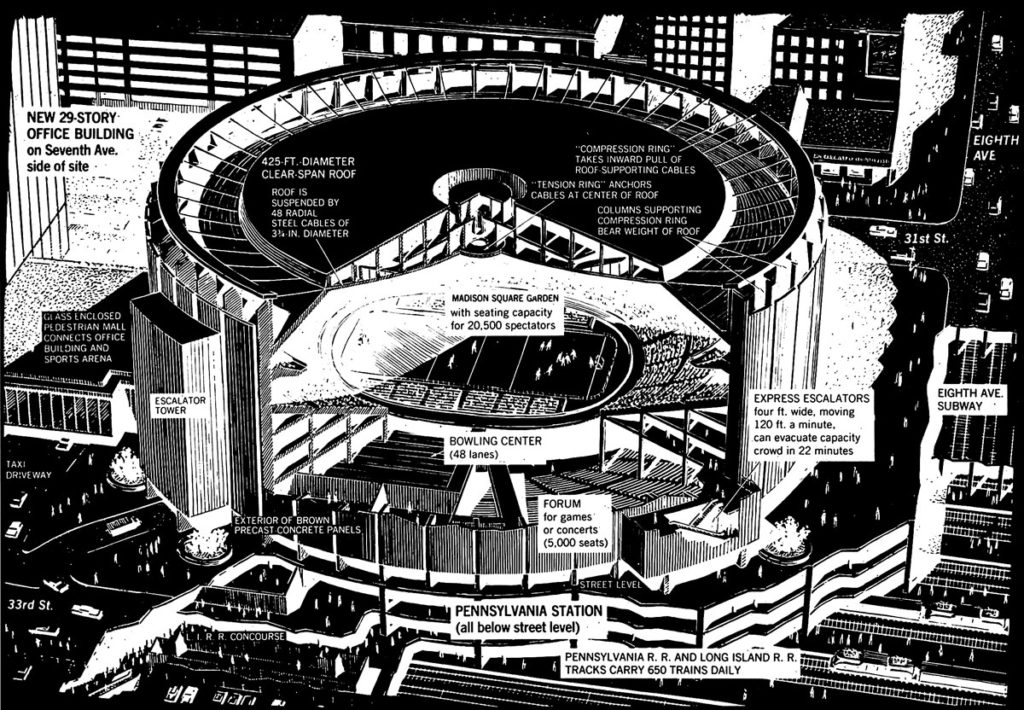

But the shortcomings became apparent over time, and by the 1960s it was time for New York City to explore a new arena. The answer was a new arena and office tower at the Penn Station site–the fourth Madison Square Garden. Preservationists decried the demolition of the McKim, Mead and White (yes, Stanford White, ironically) Beaux-Arts masterpiece to make way for a new Penn Station and Madison Square Garden; opposition to this construction led to the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission and likely saved Grand Central Terminal from a similar fate. And while Madison Square Garden has been updated and modernized since that 1968 opening, the new Penn Station started life as a terrible experience and only got worse over the years. An ideal resolution would keep MSG as it is and developing new terminal space in adjoining blocks, a la the resuse of the old Farley post office space as a train/subway terminal.

So there’s lots going on regarding MSG, but so far it’s all just wishful thinking—the city can’t get on the same page with a developer on the parameters of a plan, much less come up with a proposal that could seriously engage MSG officials. So take Fisher’s statements for what they are: a willingness to look at any plan that would keep Madison Square Garden near its current location, but certainly no commitment to more.

RELATED STORIES: New Penn Station megadevelopment announced; where will Madison Square Garden fit in?; New Madison Square Garden plan proposed