One of the Stanley Cup’s greatest charms is this: Though it is now given annually to the National Hockey League’s champion, it predates the NHL’s existence. It was purchased for 10 guineas by Sir Frederick Arthur Stanley in 1892 in order to be awarded to Canada’s best hockey team, though this criteria loosened in the next century. The first American team to win the Cup was the 1917 Seattle Metropolitans. The next year, 1918, the NHL was born.

It is a fact, then, that the proud city of Seattle, presented with its first NHL franchise in a unanimous 31-0 vote by the league’s Board of Directors on December 4 and scheduled to join the league in 2021, already has its name on the Stanley Cup.

The green, white, and red striped Metropolitans (or the Mets, as a future Major League Baseball moniker would also be abbreviated a little over a half-century later) played in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) from 1915-1924, founded by brothers Frank and Lester Patrick, each a future Hockey Hall of Famer. Frank was nicknamed the “brains of modern hockey.” Among his numerous innovations still in use, he introduced the blue line, the forward pass, the modern playoff system. Together with Lester, one of the Mets’ best players, Frank also put numbers on the players’ sweaters, created the penalty shot, and originated the assist.

The heart of the Mets was their coach, Pete Muldoon, who strengthened his club with the signings of future Hall of Famers goaltender Hap Holmes, forward Frank “the Flash” Foyston, and forward Jack Walker, each stolen away from the Toronto Blueshirts. At the ripe old age of 30, Muldoon steered his Mets to their 1917 PCHA title with a 16-8 record, including a memorable 16-1 rout of Spokane in early February. They clinched the Stanley Cup impressively, steamrolling the NHA’s powerful Montreal Canadiens and legendary goalkeeper Georges Vezina, 9-1, to win the series, 3 games to 1, in front of an overflow crowd at the Seattle Ice Arena. Bernie Morris, who had led the PCHA with 37 goals in the regular season, scored six times in the victory. As the Seattle Times reported the next day, “The lexicon of sport does not contain language adequate to describe the fervor of the fans who saw Seattle triumph last night.”

A rematch with the Canadiens for Lord Stanley’s Cup arrived two years later, but with the championship still undecided due to a tie and two wins apiece, all but four of the Canadiens fell victim to the terrible Spanish Flu epidemic. Muldoon agreed to call off the remainder of the series and co-champions were declared, with both teams’ names inscribed on the Stanley Cup. On April 5th in Seattle, days after the series was cut short, Montreal’s Bad Joe Hall, the career leader in Stanley Cup games at the time and a future Hockey Hall of Famer, succumbed to the combination of flu and pneumonia. He was 37 years old.

The Mets had one last try at the Cup in 1920, taking on the NHL’s rising powerhouse Ottawa Senators, who were scheduled to host every game in the series. The Sens won the first two games of the series at home, but Seattle struck back to win in Ottawa. Game 4 was moved to an artificial ice surface at Toronto’s Arena Gardens due to poor home ice conditions for the Senators, and the Mets won again to force a decisive Game 5 in Toronto. But the final game was not close, a 6-1 Ottawa victory behind a Jack Darragh hat trick. Four years later, the Metropolitans folded and the PCHA was no more. Seattle’s Ice Arena became a parking garage.

The Patrick brothers tried again with the Pacific Coast Hockey League (PCHL) in 1928-29, opening a new arena in Seattle, the Civic Ice Arena, and a new team in the Emerald City, the Seattle Eskimos. Pete Muldoon was back as well, this time as a financial backer and part owner. Muldoon had left the Pacific Northwest in 1926 for a seemingly golden opportunity as the first ever head coach of the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks (then the Black Hawks), but, wrote Morey Holzman in the New York Times, he “tired of interference from the Blackhawks’ president and owner, Frederic McLaughlin, and gave two weeks’ notice with 14 days left in the season.” Thus began Chicago’s mythical Curse of Muldoon, which beset the Blackhawks until their first first-place finish in 1966-67 and their first first-place finish/Stanley Cup title in the same season in 2009-2010.

Muldoon’s renewal of acquaintances with the Patrick brothers was short-lived. On March 13, a heart attack ended his life while on the road at Tacoma looking at rink locations for a potential PCHL expansion team. The Eskimos lost in the league championship series in 1929, missed the playoffs in 1930, and then lost to Vancouver in the 1931 postseason before closing operations.

The next Seattle pro hockey franchise had a familiar name for modern audiences: the Sea Hawks. Not the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks, mind you. They were still four decades away. The Northwest Hockey League’s Seattle Sea Hawks began play in 1933. Former Metropolitans great Frank “the Flash” Foyston balanced a side career of turkey farming with coaching the Hawks to the Northwest Hockey League finals in 1935, where they lost to Vancouver, 3 games to 2.

And then The Flash, stunningly, was fired.

Ah, but 10 games (and seven losses) into the following season, The Flash was back and the Sea Hawks soared to the 1936 Northwest Hockey League championship, defeating Vancouver, 3 games to 1, giving the city its second outright crown.

The Sea Hawks’ success was consistent, limited, and fleeting. By 1939, they had made four trips to the championship series in six seasons, but still only boasted the one title. By 1940, they were renamed the Olympics. By 1941, they were no more.

There were other teams in the years to come: The Seattle Ironmen in the 1940s, who were renamed the Seattle Bombers in 1952, who became the Seattle Americans in 1955, who were revamped as the Seattle Totems in 1958, a change credited in part to Seattle Times sports writer Hy Zimmerman. Seattle was strong, with stars like Guyle Fielder, who notched a record-breaking 122 points in 1956-57 as an American and then followed up with 119 points in 1958-59 as a Totem. Buoyed by Fielder, supplemented by a trio of 30+ goal-scorers in Marc Boileau, Val Fonteyne, and Rudy Filion, and coached by future Philadelphia Flyers architect Keith Allen, the Totems marched through a four-game sweep of the Calgary Stampeders to win the 1959 Western Hockey League championship, soon to be renamed the Lester Patrick Cup. It was the Totems’ first of three titles and five championship series visits, including back-to-back championships in 1966-67 and 1967-68.

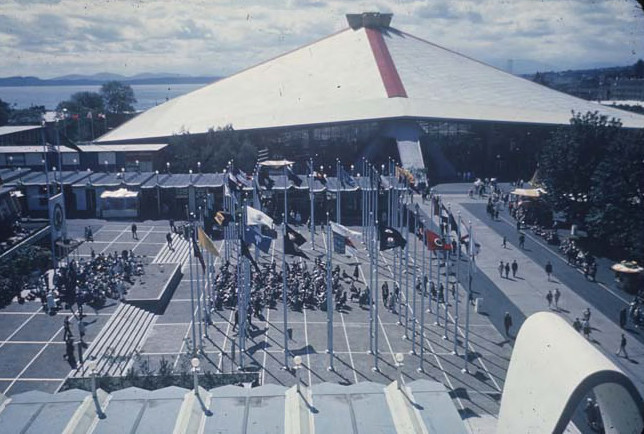

The Totems received a challenge of a different nature on Christmas Night 1972, becoming the first American pro team to play the Soviet national team. A crowd of 12,367 attended the historic exhibition at the Seattle Center Coliseum (later renamed KeyArena). The Totems battled back from an early 3-0 deficit to tie the game at 4-4 but surrendered five straight scores in a 9-4 loss. Said Paul Raymer afterward, “I would have played them for nothing. Just for the enjoyment and experience to say you’ve played them.” It was the first game of a four-exhibition Western Hockey League trip for the Soviet squad, which finished undefeated.

A year later, looking to build on the success of an international opponent, the Totems and the WHL welcomed in the Czech National Team in addition to the Soviets. Seattle triumphed first over the Czechs on Christmas Night 1973, 6-4, and then stunned the Red Army at a roaring Coliseum on January 5th, 1974, 8-4, behind a Don Westbrooke hat trick.

For those working behind the scenes, this all seemed part of a preamble to something much larger. With an exciting young NBA franchise in town since 1967, the SuperSonics, Seattle aspired to receive NHL, NFL, and MLB franchises as well. The National Football League awarded the city a franchise in June 1974, with the Seattle Seahawks opening play in 1976. In Major League Baseball, the Seattle Pilots had spent only one year in the Emerald City before transplanting themselves to Milwaukee. The City of Seattle and the State of Washington sued the American League, and the Seattle Mariners arrived in 1977.

As far as the NHL was concerned, it too looked like a done deal. On June 12th, 1974, the following headline appeared in the New York Times: “N.H.L. Gives Franchises to Denver, Seattle for ’76.” With the announcement, the Western Hockey League shut down operations and the Totems joined a new circuit, the Central Hockey League, to wait out their arrival in the National Hockey League.

But, wrote Sean Indoe in “The Down Goes Brown History of the NHL,” “it quickly became apparent that the money wasn’t going to be there, and months after the Totems folded in 1975, the NHL pulled its offer off the table. The Seattle ownership group sued, and the case dragged on for years before the league finally won.”

So it was that the next chapter in Seattle’s hockey history was not the highest level of the sport, but junior hockey: the Seattle Breakers of the Western Canada Hockey League (now the Western Hockey League), who played eight seasons beginning in 1977, and then were renamed the Thunderbirds entering the 1985-86 campaign. They have kept the name ever since, producing such future NHL players as Patrick Marleau, Chris Osgood, and Shea Theodore. At one time they played at KeyArena at Seattle Center, the former home of the Seattle Totems; now the Thunderbirds skate at the accesso ShoWare Center in Kent.

The Seattle Thunderbirds have won only one title in team history. It came dramatically last year, May 14th, 2017, with Alexander True’s goal lifting the Thunderbird’s to a 4-3 overtime victory over the Regina Pats in Game 6 of the WHL Championship Series — 100 years after the Metropolitans of the Patrick brothers, Pete Muldoon, Bernie Morris, and Frank the Flash gave Seattle its first hockey title.

And now, the next chapter. When 2021 rolls around, the city will have its first professional hockey team since the Totems, the first NHL team that the city has ever seen.

There was a special guest at the official announcement, joining the NHL Seattle ownership group, a guest who brought the entire Seattle hockey legacy full circle. Her name was Beverley Parsons, age 83, a resident of Bellevue, a niece of Frank and Lester Patrick. Over a century earlier, it was her uncles who first brought hockey to the Emerald City and delivered the United States its first Stanley Cup.

Now, with Parsons and the Pacific Northwest avidly watching, Seattle will soon have the chance to win the Cup again.

This article originally appeared in the weekly Arena Digest newsletter. Are you a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the free weekly newsletter